Call it coincidence, serendipity, an aligning of the planets—whatever the term, the moment was creepy and amusing all at once. I was beavering away in the basement research room at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, in Yorba Linda, a suburb of Los Angeles, when Henry Kissinger twice came into view—in the flat, cursive form of Nixon’s scrawl in the margins of the book I was reading, and then in the rounder corporeal form of the man himself, in the hallway outside the door.

Kissinger, the last surviving member of Nixon’s Cabinet, was in Yorba Linda last fall for two reasons: to speak at a fundraising gala for the Richard Nixon Foundation and to promote a book he had published earlier in the year, at the improbable age of 99. The book, Leadership, contains an entire chapter in praise of Nixon, the man who had made Kissinger the 20th century’s only celebrity diplomat.

I was there to gather material for a Nixon book of my own. I had been nosing around in a cache of volumes from Nixon’s personal library. I was particularly interested in any marks he may have left in the books he’d owned. From what I could tell, no one had yet mined this remarkably varied collection, more than 2,000 books filling roughly 160 boxes stored in a vault beneath the presidential museum. Taken together, they reflect the broad range of Nixon’s intellectual curiosity—an underappreciated quality of his highly active mind. To give an idea: One heavily underlined book in the collection is a lengthy biography of Tolstoy; another is a book on statesmanship by Charles de Gaulle; another is a deep dive into the historiography of Japanese art. Several fat volumes of The Story of Civilization, Will and Ariel Durant’s mid-century monument to middlebrow history, display evidence of attentive reading and rereading.

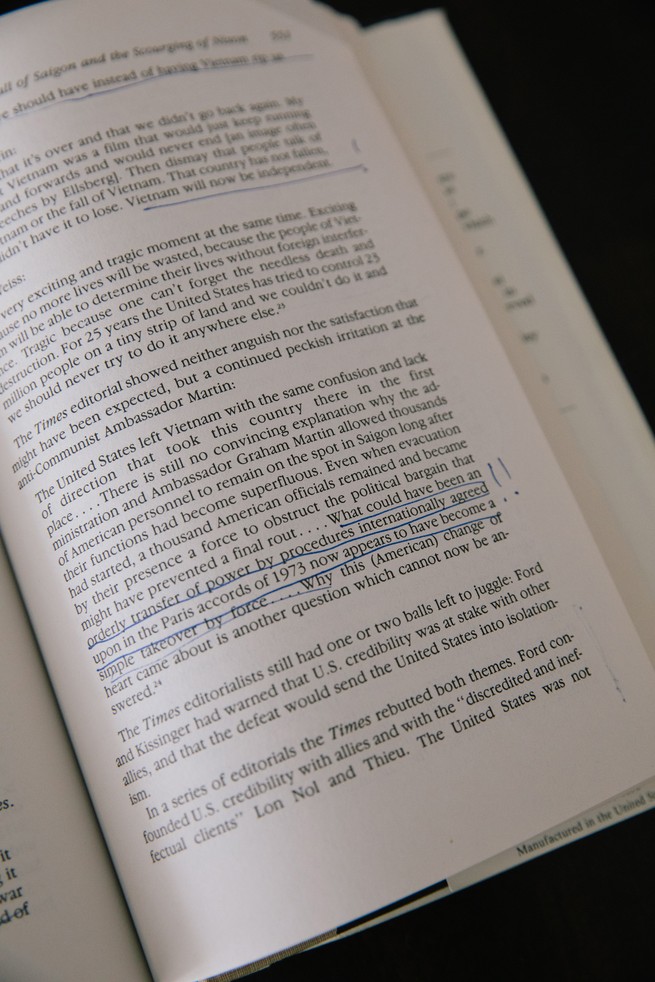

Every morning a friendly factotum would wheel out a gray metal cart stacked with dusty boxes from Nixon’s personal library. On the afternoon Kissinger arrived, I had worked my way down to an obscure book published in 1984, a decade after Nixon left the White House. A significant portion of Bad News: The Foreign Policy of The New York Times, by a foreign correspondent for the New York Daily News named Russ Braley, is a blistering indictment of the Times’ coverage of the Nixon administration. In Braley’s telling, the Times’ treatment swung between the unfair and the uncomprehending, for reasons ranging from negligence to malice.

The book had found its ideal reader in Richard Nixon. The pages of his copy were cluttered with underlining from his thick ballpoint pen. It occurred to me, as I followed along, that Nixon was being brought up short by his reading: Much of the material in Bad News was apparently news to him.

My reading was interrupted by a commotion outside the research room. I stuck my head out in time to see Kissinger and his entourage settling into the room across the hall. A group of donors and Nixonophiles had gathered to hear heroic tales of Nixon’s statecraft.

I dutifully returned to Braley. When I got to a chapter on Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers, I found an unmistakable pattern: Most of Nixon’s markings involved the man holding court across the hall. And Nixon wasn’t happy with him. Kissinger, Braley wrote, had actually invited Ellsberg to Nixon’s transition office in late 1968 to explicate his dovish views on Vietnam, more than two years before the Papers were released. Nixon’s pen came down: exclamation point! Kissinger gave Ellsberg an office in the White House complex anyway, for a month in 1969—a stone’s throw from the Oval Office. Slash mark! Kissinger spent his evenings “ridicul[ing]” Nixon “in private conversations with liberal friends.” This last treachery summoned the full battery of Nixon’s marginalia: a slash running alongside the paragraph, a check mark for emphasis, and a plump, emphatic line under “liberal friends.”

Still, Braley went on, when the Pentagon Papers were leaked, their publication alarmed Kissinger, because they posed a “double threat” to national security and to the conduct of foreign policy. “And to K!” Nixon wrote in the margin.

The contrast between Nixon’s bitter hash marks about Kissinger from the 1980s and Kissinger’s present-day celebration of his old boss offered a lesson in the evolving calculation of self-interest. It also conjured the image of a solitary old man in semiretirement, learning things about a now-vanished world he’d once thought he presided over. It happened often in the reading room in Yorba Linda: With unexpected immediacy, the gray metal cart carried the past into the present, in small but tangible fragments of Nixon himself.

The task of a marginalia maven is at right angles to the task of reading a book: It is an attempt to read the reader rather than to read the writer. For several decades now, scholars have been swarming the margins of books in dead people’s libraries. Those margins are among the most promising sites of “textual activity,” to use the scholar’s clinical phrase—a place to explore, analyze, and, it is hoped, find new raw material for the writing of dissertations. Famous readers whose libraries have fallen under such scrutiny include Melville and Montaigne, Machiavelli and Mark Twain.

A book invites various kinds of engagement, depending on the reader. Voltaire (whom Nixon admired, to judge by his extravagant underlining in the Durants’ The Age of Voltaire) scribbled commentary so incessantly that his marginalia have been published in volumes of their own. Voltaire liked to argue with a book. Nixon did not. He had a lively mind but not, when reading, a disputatious one; he restricted his marginalia almost exclusively to underlining sentences or making other subverbal marks on the page—boxes and brackets and circles. You get the idea that he knew what he wanted from a book and went searching for it, and when he found what he wanted, he pinned it to the page with his pen (seldom, from what I’ve seen, a pencil).

In his method, Nixon resembled the English writer Paul Johnson. I once asked Johnson how, given his prolific journalistic career—several columns and reviews a week in British and American publications—he managed to read all the books he cited in his own very long and very readable histories, which embraced such expansive subjects as Christianity, ancient Egypt, and the British empire. His reaction bordered on revulsion at my naivete. “Read them?!” he spat out. “Read them?! I don’t read them! I fillet them!” As it happens, Nixon was an avid reader of Johnson, whose books he often handed out to friends and staff at Christmastime.

John Adams, another busy producer of marginalia, liked to quote a Latin epigram: Studium sine calamo somnium. Adams translated this as: “Study without a pen in your hand is but a dream.” Nixon acquired the pen-in-hand habit early, as his surviving college and high-school textbooks show, and he kept at it throughout his life. For Nixon, as for the rest of us, marking up books was also a way of slowing himself down and attending to what he read. He was not a notably fast reader, by his own account, but his powers of concentration and memorization were considerable. Going at a book physically was a way of absorbing it mentally.

One of the most heavily represented authors in Nixon’s personal library is Churchill, whom Nixon revered not only as a statesman but also as a historian and an essayist. Nixon’s shelves sagged with Churchill’s multivolume histories and biographies: The World Crisis, Marlborough: His Life and Times, The Second World War, A History of the English Speaking Peoples. Churchill’s Great Contemporaries, a series of sketches he wrote in the 1920s and ’30s sizing up roughly two dozen friends and colleagues, was clearly a favorite. When I retrieved Nixon’s copy from a box, I found it dog-eared throughout.

Nixon’s tastes ran heavily toward history, but he could be tempted away from the past to a book of present-day punditry, if the writer and point of view were agreeable. According to a report in Time magazine, when half a million citizens descended on Washington, D.C., in November 1969 to protest the Vietnam War, Nixon holed up in his private quarters with a book called The Decline of Radicalism: Reflections on America Today. The book, slim and elegant, had been sent to Nixon by its author, the historian Daniel Boorstin.

Judging by his notations, Nixon was interested less in Boorstin’s turgid cultural analysis of “consumption communities” and more in his thesis that the ragged protesters gathering outside the White House fence constituted something new in American history: They were not radicals at all but nihilists. Nixon brought out the pen, and in Yorba Linda, a continent and decades away from his White House hideaway, I could still feel the insistent furrow of his underlining on the page. He marked several consecutive paragraphs in a section called “The New Barbarians,” in which Boorstin criticized protesters for their “indolence of mind” and “mindless, obsessive quest for power.”

People read books for lots of reasons: instruction, pleasure, uplift. This was Nixon reading for self-defense.

The book I most wanted to see in Yorba Linda was Nixon’s copy of Robert Blake’s biography Disraeli (1966). A re-creation of Nixon’s favorite room in the White House was one of the Nixon museum’s prime exhibits when it opened, in 1990, a few years before Nixon’s death. (It has since been redesigned.) Nixon himself chose Disraeli to rest on his desk for the public to see. The book was given to him during his first year in the White House, in 1969, by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a Harvard professor, prominent Democrat, and future U.S. senator from New York. To the surprise of just about everybody, the year he took office, Nixon made Moynihan his chief domestic-policy counselor, a counterpart in those early days to Kissinger as head of the National Security Council. Despite Nixon’s enduring image as a black-eyed right-winger, his political ideology was always flexible, if not flatly self-contradictory.

Moynihan the liberal hoped to persuade Nixon the hybrid to take Benjamin Disraeli, the great prime minister of Victorian Britain, as his model. Disraeli was a Tory and an imperialist, and at the same time a social reformer of vision and courage. According to Moynihan, Nixon read the book within days of receiving it. Soon enough, the president was calling himself a “Disraeli conservative.” The precise meaning of the tag was clear to Nixon alone, but we can assume it underwent a great deal of improvisation and revision as his presidency wore on.

Disraeli’s appeal to Nixon went beyond his light-footed ideology. Speaking to his Cabinet at a dinner one evening in early 1972, Nixon called Disraeli a “magnificent” politician. Now, he went on, the “fashionable set today would immediately say, ‘Ah, politicians. Bad.’ ” As he saw it, the “fashionable set”—the epithet, suffused with reverse snobbery and class resentment, is pure Nixon—believed that politicians disdain idealism and think nothing of principle. “But,” Nixon said, “the pages of history are full of idealists who never accomplished anything.” It was “pragmatic men” like Disraeli “who had the ability to do things that other people only talked about.” Nixon, who had never shied away from calling himself a politician, wanted to see himself in Disraeli, or at least in Blake’s Disraeli—this “classic biography,” to which, he told his Cabinet, he often turned for inspiration on sleepless nights. And here the book was, Nixon’s own copy, at the top of my growing stack in Yorba Linda.

Disraeli is packed with observations about political tradecraft. They are penetrating, specific, and cold-blooded. The little dicta come from both the biographer and his subject. “He was a master at disguising retreat as advance,” Blake wrote approvingly. Nixon underlined that sentence, and then this one from Disraeli’s contemporary Lord Salisbury: “The commonest error in politics is sticking to the carcasses of dead policies.”

A line, a check mark, a circle—why Nixon deployed one notation and not another for any given passage is a question as unanswerable as “Why didn’t he burn the tapes?” But it was politics that always caught his eye, and activated his pen. Disraeli, Blake wrote, “suffered from a defect, endemic among politicians, the greatest reluctance to admit publicly that he had been in the wrong, even when the fault lay with his subordinates.” Another from Blake: Successful politicians “realize that a large part of political life in a parliamentary democracy consists not so much in doing things yourself as in imparting the right tone to things that others do for you or to things that are going to happen anyway.”

Should we take marked passages like these, with their ironic acceptance of the fudging and misdirection called for in the political arts, as a gesture toward self-criticism on Nixon’s part? Probably not: Nixon knew himself better than psycho-biographers give him credit for, but self-awareness is not self-criticism. In his chosen profession, he took the bad with the good, and his casual, creeping concessions to the seamier requirements of politics are what eventually did him in.

If you go looking for them, you can see reflections of Blake’s Disraeli throughout Nixon’s presidency, encapsulated in enduring phrases here and there. It was in Blake that Nixon came across Disraeli’s famous description of “exhausted volcanoes.” Disraeli coined it to disparage the feckless time-servers in William Ewart Gladstone’s cabinet after they had been in office a few years. Nixon underscored not only “exhausted volcanoes” but the rest of the passage from Blake’s text: The phrase, Blake writes, “was no mere gibe … For the past year, the Government had been vexed by that combination of accidents, scandals and blunders which so often for no apparent reason seem to beset an energetic administration in its later stages.”

Nixon feared the same fate for his second term—a loss of energy and direction. The day after his landslide reelection, in 1972, he called together his Cabinet and senior staff. He told them of Disraeli’s warning about “exhausted volcanoes.” And then, with his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, serving as the lord high executioner, he demanded their resignations en masse.

Not everything in Blake’s Disraeli caught Nixon’s interest; certainly not everything was useful to him. As I paged through, I saw there were many longueurs, stretches of several dozen pages, sometimes more, where no filleting of any kind happened. And then—inevitably, suddenly—Nixon the reader is seized by passages of sometimes thunderous resonance, and the pen is again called into play.

“Disraeli,” Blake writes, “really was regarded as an outsider by the Victorian governing class.” One can almost see Nixon sit bolt upright and pick up his pen. This is the same ostracism that Nixon himself felt keenly throughout his personal and professional life, in fact and in imagination. The following page and a half, discussing the disdain of the “élite” for Disraeli, is bracketed nearly in its entirety. Some sentences are boxed. Some passages, like this one, are underlined as well as bracketed:

Men of genius operating in a parliamentary democracy … inspired a great deal of dislike and no small degree of distrust among the bustling mediocrities who form the majority of mankind.

The antagonism of the elites was not the determining fact of Disraeli’s career, but both biographer and subject perceived its profound effects, and so did the man reading about it 90 years after Disraeli’s death. As president, Nixon felt himself similarly situated: the political leader of an imperial nation, highly skilled, aching for greatness, yet in permanent estrangement from the most powerful figures of the politics and culture that surrounded him, nearly all of whom he judged, as Disraeli had, “bustling mediocrities.”

When reading about the elites, Nixon pressed the ballpoint deep into the page. We marginalia mavens, tracing our fingers across the lines today, can only guess, of course. But it may be that in 1969, sitting in the reading chair in his White House hideaway, he already sensed that this was not bound to end well.

This article appears in the October 2023 print edition with the headline “Nixon Between the Lines.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.